by Helene Baron-Murdock

A group of amateur mycologists in the pristine timberlands of R. K. Turas State Park found a freshly severed big toe at the base of a pine where amanita muscaria were growing. At first the blood red end was indistinguishable from the bright red of the mushroom’s cap. Then blood dripping from nearby ferns only added to their initial horror.

Donavan was a little late but he’d already heard the initial report. Now he was watching Derrick Voss, the new Captain of Detectives, go through the power point on the screen in semi darkened Conference Room Two. The entire squad was in attendance for the briefing, excepting Rick Nelson who had taken time off while his wife had their first child. The grizzly aspect of the murder had caught everyone’s attention.

Voss was pointing to the photos of numbered placards each designating a body part strewn across the forest floor. “They found the head” he said referencing another slide, “floating down the Acre River near Sharon’s Crossing on some kind of rude raft made of branches.” He paused to give Donovan a nod and then said, “Glad you could make it, Detective.”

Voss was pointing to the photos of numbered placards each designating a body part strewn across the forest floor. “They found the head” he said referencing another slide, “floating down the Acre River near Sharon’s Crossing on some kind of rude raft made of branches.” He paused to give Donovan a nod and then said, “Glad you could make it, Detective.”

Donovan hadn’t liked Voss when he first met him, an outside promotion hire from a department down south. And now he liked him even less. He spotted the subtle twist of Lieutenant Mike Jackson’s lips in a grimace, the dive of the lines of his forehead into a frown. The Loot was ten times the cop that Voss was and should have been the automatic choice for promotion after Krazy Ed Kryzinski retired. Because Jackson was a black man that wasn’t going to happen. Voss was the new breed of cop, white and ambitious, giving truth to that old saying, meet the new breed, same as the old breed. Or something like that. “HR took longer than expected, Cap, lots of paper work to read through and sign.”

“Try not to make a habit of it,” Voss admonished and turned back to the PowerPoint. “These three women are our primary persons of interest.”

Donovan glanced at the head shots, a trio of pretty hard to look at gals, and then at his squad mates seated around the table looking at him with expressions of questioning disbelief and surprise. Had he finally done it? Burdon gave him a subtle power fist and Townsend flashed a thumbs up. He had filed his retirement papers.

Back at his desk, Donovan cleared the file he’d been looking through, an old case that had caught his interest dating from back before he’d made detective. He’d been a Deputy then, patrolling the rural country around Hades Acre Lake in the northern part of Weston County, when he caught the report of the ten-fifty four over the unit’s radio. And he was one of the first officers on scene. He wasn’t going to forget the flayed condition of the body in this lifetime. Something about the current case was giving him pause. And his phone rang. It was Veronica, the Sheriff’s secretary.

“I hear that congratulations are in order.”

“Are you sure you don’t want to talk to Nelson. It’s his wife’s having the baby.”

“I’m going to miss your smart mouth.”

“That’s more like it.”

“The Sheriff would like to see you in his office.”

“Now?”

“Now.”

Donovan avoided elevators. You never knew who you were going to meet on an elevator and he always felt so exposed when the doors parted at the destination. He took the stairs four flights up to the top floor passing through the administration wing of Justice Hall where he was familiar with many of the employees, mostly women, and who greeted him with more congratulatory best wishes. He muttered his thanks and appreciations and waved back in greeting. Veronica was on the phone when he got to the Sheriff’s outer office but she smiled and mimed him to go right in.

He hadn’t been expecting champagne or even cake so he wasn’t disappointed, but he was surprised to see Voss seated in one of the two chairs in front of Phil’s large ornate frieze-like desk.

Phil greeted him without getting up from behind the desk but Donovan noticed the crutches leaning against the cabinet behind and figured that the gout must be acting up again.

“Have a seat, have a seat,” Phil insisted. “You know Captain Voss, of course. I was just telling Derrick that it was a tough break to be less than a week on the job and get hit with this horrendous crime, murder, repulsive dismemberment. It’s a tough job and it isn’t made any easier with the pressure from the DA’s office. And the media. To get a handle on this outrage in a hurry. And I assured him that he had a crack squad of experienced detectives already on the case, especially you, Jim, you’re one of the old timers, you know the lay of the land, and you’ve established impeccable sources.” Phil paused a breath. “Are you familiar with the three women who are being held as witnesses? Are we getting anywhere with them?”

Donovan shook his head. “I saw the mugs, runaways maybe. My guess, by the location, living rough on the Bare Ranch.” He referenced the notebook he’d slipped from his jacket pocket. “Melanie, Dora, and Laurel, no last names because last names are patriarchal, so I hear.” He recalled his reading of the booking photos, the insolent stare of the leader, the vacant stare of the next smartest, and the clueless stare of the last. Dumb, dumber, and, dumbest, the three ingredients for mayhem. “You won’t guess who they’ve been talking to.”

The sheriff winced like his gout was acting up. “May Naddy?”

The sheriff winced like his gout was acting up. “May Naddy?”

Voss leaned toward the desk’s edge after glancing a scowl at Donovan. “I’ve got Jackson on the interview panel with a couple of the other senior men, Sheriff. Detectives Donovan and Nelson are chasing down identification on the victim. I’m sure they’ll piece it all together.”

Phil roared, “Piece it together! That’s a good one, Voss!” He thumped his desk and wheezed out another laugh. Donovan figured that maybe the gout medication was making the boss loopy, not his usual high and mighty aloofness, or maybe he’d self-prescribed a three martini lunch. And he watched Voss’s face go blank and then register a flicker of recognition as he realized what exactly the “good one” was.

“Nelson’s on family leave. His wife just had a baby.”

Voss glared at Donovan, obviously displeased at being corrected. “I thought I had ordered all critical staff back on duty. Why does Nelson think he’s excluded from that order?

The Sheriff nodded sagely. “His job was done nine months ago, why didn’t he take the time off then?”

Donovan ignored the remark, more annoying than inappropriate and confirming his hunch that the boss had had one too many olives with his martinis. “It doesn’t take two of us to get the ID on the vic. I can have the techs work up a composite sketch from the remains of the head and get the picture distributed through the usual channels by the end of the day.”

“I would expect no less, Detective, but you have missed the point. When I make an assignment of personnel to staff a vital function in an investigation, I expect them to report for duty no matter the circumstances.” Voss had turned to him, grim faced, and rose, “But you’re retiring soon, is that correct? I hope we can have this cleared up before then and you can retire on a high note.” Nodding to the Sheriff, he said “I have to get back for a meeting with the Medical Examiner. I hope you’ll consider my suggestions for streamlining the unit.”

After Voss had left, Phil Collins cleared his throat and raised his eyebrows. “So you went and did it. Finally going to pull the plug. I’m kinda of jealous. What are your plans for, you know, after?”

“I’m not going to be dead, Phil. Contrary to what people believe, there is life after retirement. I’ll finally have the time to work on fixing things around the house, remodel, dig up that slab covering most of my backyard. Travel, maybe, go east, Baltimore, look in on Marion.”

Phil wagged his chin leaning back in his chair, eyes narrowing. “Marion, that the colored gal you were dating, from the hospital?”

Any regrets about retiring from a job that had been his life for over 30 years evaporated in the heat of his slow boil. “Yeah, the ER nurse.”

Phil leaned forward. “We go back a ways, Jim. We were rookie deputies together. You were a module or two ahead of me in the Academy, I remember. We may have had our run-ins over time, but I knew I could always count on you doing the job. I think sometime that temper of yours can get in the way, cloud your judgement. I also think you picked a good time to go out. Voss is more of a manager than a cop, and I don’t doubt that you and he would bump heads over proper or improper procedure. If you get my drift.

“Anyway, just to say I’m going to hate to lose your years of experience and knowhow on a case.” The Sheriff paused to look down as if he were holding a hand of cards. “So I’m going to put this on the table for you to consider.” He looked up. “Retired annuitant.”

“Doing what? Paperwork?”

“Yeah, pretty much. Cold cases, sorting, filing, creating a data base.”

Donovan shook his head. “I don’t know anything about data bases. Besides I thought Krazy Ed was going to do that. Wasn’t that why he retired? It would give him time to solve the case of the century or last century, his obsession with the Lopes clan.”

Tim shook his head. “The problem with Krazy Ed is that he’s crazy. Or to put it more politely, demented.”

“That’s not more politely. You mean dementia?”

“Keep that under your hat, but it was a medical retirement.”

“I don’t know. It sound boring, a lot like my current job which if it weren’t for the occasional axe murder would be unbearable.”

Collins chuckled his acknowledgement of the dig from the dark side. “You don’t have to commit to anything just yet. I can get a grant from the State through the Justice Department for Data Enhancement, meaning put together a coherent archive of cold cases with links to a nationwide network. I need an experienced officer who knows how to read a file and I can hire an assistant to do the data entry. We’re a small county. We don’t have a big cold case backlog. You can do it in your spare time. What have you got to lose?”

“Spare time.”

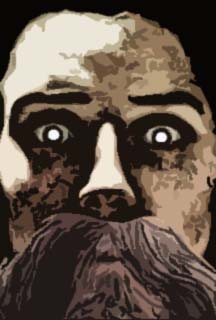

Mary Fisher, the crime scene tech, wore her own version of scrubs, a cross between a nurse and a lab tech, utilitarian blue pants and jersey under a long white lab coat. She was pointing at the image on the screen. “I took photographs of the head from various angles and then fed them into this reconstruction program that puts it together in a 3D image. He was missing an ear, lower lip, part of the nose, the whole left side of his cheek, and the hair from that side of his head.”

“Pretty gruesome.”

“Vehicle accidents are worse. So I’ve heard.” Mary was plumpish, dark hair almost always in a braid pinned in a bun at the back of her head, quiet brown eyes, diffident in the way of her people, and with a quiet way of speaking. “So far, it’s just bits and pieces. Chunks, like someone or something torn up a loaf of bread and dipped in tomato sauce. We haven’t recovered the torso. Nor the hands. We can’t identifying him by fingerprints until we find his fingers.”

“You’re sure it’s a him.”

Mary colored a little, her lips clamped together. She was used to Donovan’s banter. “Unless he’s a bearded lady.” She indicated the composite on the screen and the obvious beard swathing the jaw of the otherwise wild haired gaunt visage depicting what could only generously be described as a vacant eyed mad man. “And one of the bits we found would confirm his gender.”

Donovan nodded and smiled. He’d had his fun. He’d known Mary since she was hired a dozen years ago when he was just finishing up his stint in narcotics and moving on to Violent Crimes, or Robbery Homicide, as it was known back then. And she’d been Mary King in those days, newly engaged to Jay Fisher. After he’d got to know her a little better, he’d inquired idly as to why she hadn’t hyphenated her name so she could be Mary King-Fisher. He thought he was being cute. Her answer had shut him up. “That is not his clan. He is an otter.”

“Were you part of the recovery team?”

She nodded, “Yeah, I photographed most of the physical evidence and then came back here to prep the lab. Why?”

“You familiar with the area?”

“It is a good place for mushrooms. Of all kinds. My uncle would load us up in his truck and we would range through the forest hillside. This was before the State made it a park. But then, better that than condos. He taught us little songs that we would sing when we picked the mushrooms. They included a description and a thank you to be sung when we lifted one out of the ground. We were only allowed to pick the edible ones. The older boys picked the stronger ones and sold them at the High School.”

“Schrooms?”

One raised eyebrow answered the question. She handed him the printed sketch of the 3D model and said, “I hear you put in your paper. Sorry to see you go.”

He tugged at the sheet and she released the sketch. “I thought that was privileged information.”

“My cousin works in HR.”

Donovan stepped into Mike Jackson’s office with a handful of sketches to be distributed by the shift commander to the patrol units. He’d started a facial recognition search at his desk and was waiting for results. The Lieutenant had the same mug shots of the three women he’d seen earlier at the briefing up on his monitor. He shook his head and looked up at Donovan. “What would make them do such a thing? How could they do such a thing? They’re just women. Tear him to pieces like that.”

“They admit it? Maybe they had help.”

“Bloodied clothes would be the indication. And they’re not making much sense. Like they’re from another dimension or reality.”

“Think it could be ritual?”

“I don’t want to rule it out, but Voss isn’t interested in that angle. He wants straight out drug induced murder and mayhem. Reads better in the press, and besides ritual always leaves too much unanswered.” Jackson indicated the papers in Donovan’s hand. “Something you want to see me about, Jim?”

“I’ve got a facial recognition match in progress, thought you might want to take a look at the sketch that’s going out to the field.”

“I’ve got a facial recognition match in progress, thought you might want to take a look at the sketch that’s going out to the field.”

“Now there’s a face you don’t want to be staring back at you in the mirror.”

“Yeah, sociopath poster boy of the year.”

“How old you think he could be?”

“Anywhere from late forties to early sixties.”

“Right about our ages. I hope I look better than that when I go.”

“Yeah, he looks like he’s been rode hard and put away wet.”

Jackson laughed his appreciation. “Claymore?”

“Yeah, he was my sergeant years ago. I don’t know where he gets them.”

“I’d like to say, ‘last of the cowboys,’ but that isn’t so. There are newer and younger ones coming up every day.” He leaned forward, amused as Mike Jackson would ever get. “You had the rep of being something of a cowboy yourself, at least when you were in drug interdiction.”

“You have to be a cowboy if you’re going to play in that game, and you don’t have a choice. When it goes down, it goes down hard. Armed interdiction is high risk, you got to be like them but more so.”

“If that’s your logic, do you have to think like a murderer to work in homicide?”

“Most homicides are no brainers, husband, wife, ex, ex-lover, son, daughter, relative, neighbor, gang. You walk up on it, look around and you know right away which one of those Einsteins did it or knows who did it. You learn to read the scene, the people. If there are no witnesses, someone will know why, and maybe who. Unless they’re stone psychopaths, they have tells, twitches. Or come right out and confess before you ask the first question. Other times you have to negotiate. The paper work is the same, and it’s up to the DA to make the case with what I give him.”

“Well, things won’t be the same around here without you, Jim. Hell of a note to retire on, though. I hope we can wrap it up before you head out the door.”

“Unless it turns into a Krysinski case then it will never end.”

“Oh jeez, the Lopes. I’m glad I don’t have to listen to that horseshit anymore. He wasted a lot of manhours, his own, and some of the squad’s, on the Lopes Loop.”

“Collins offered me the annuitant job on cold cases. More paperwork, but I’d have an assistant to do the computer stuff.”

“That was Krysinski’s deal, wasn’t it.”

“Yeah, I don’t think I’ll take it. I don’t want to get tied down. There’s a waiting period before I can go back to drawing a county check. Hopefully I can find something that doesn’t have anything to do with asking questions of corpses.”

“I got another five before I even consider it. Be nice to go out with a promotion, but. . . .

“Yeah, I know. . .the new guy? I’m not sticking around to find out. And another thing that’s bugged me. When Krysinski retired, why didn’t Collins promote you to acting COD until the hiring freeze was lifted instead of taking it on himself? And then to promote from outside the department? What kind of message does that send?”

“You don’t have to ask. You know. And it’s the same old question. When I passed the detectives exam and placed in the first rank on the list I knew that I would never promote within the Santa Lena PD. The Chief told me right to my black face. I took the first offer that came along and that was with the Weston County Sheriff’s Office. I heard the word was out that I got the job because of the color of my skin. The Sheriff’s Office had been slammed by the grand jury for being noncompliant with County diversity guidelines. And they grabbed the first chocolate chip they could get their hands on. So maybe they were right. I did get the job because of the color of my skin. Not that it’s changed anything. And Santa Lena PD has yet to hire and retain a person of color in their sworn ranks.”

“Like you say.”

“I did my job, and I got good at it, and people that mattered said I had good leadership qualities. I think that my annual Fourth of July barbeques, where they got hammered and did stupid shit and knew that I knew they had, might have had something to do with it, too. Still when I got promoted to Lieutenant, the word going around was that I got the job because of the color of my skin. Now if I’d been made Captain of Detectives, the same thing would have been said.

“And since you weren’t.”

“Now therein lies the salt to rub in the wound, to paraphrase Willy. The irony is that you could say that I didn’t get the job, and I did interview for the position, you could say that it was because of the color of my skin.”

“Amen.”

“Your pocket is buzzing.”

Donovan retrieved his black clad device and glanced at the screen. “Ok, got an ID on the vic. He’s got paper, and. . .that’s interesting.”

“Whuzat?”

“He’s a poet.”

“Dead poet now, and as my old English Lit prof used say, the only good poet is a dead poet.”

Among the array of framed protest placards and posters urging respect for Mother Earth or face the dire consequences, the one that caught Donovan’s eye proclaimed “Braless & Lawless” superimposed over an artfully distressed representation of three women giving the power salute. Another wall was painted sky blue bisected by the darker arc of an image of Earth seen from space against which stood a set of bookshelves lined with somber spines and a sign above it that read Earth Consciousness Library crudely carved into a wide weathered plank. A patchwork of worn and frayed Indian rugs covered a slab floor around which were deployed a variety of mismatched secondhand couches and armchairs and centered on a redwood burl table piled with slick conservationist magazines.

Among the array of framed protest placards and posters urging respect for Mother Earth or face the dire consequences, the one that caught Donovan’s eye proclaimed “Braless & Lawless” superimposed over an artfully distressed representation of three women giving the power salute. Another wall was painted sky blue bisected by the darker arc of an image of Earth seen from space against which stood a set of bookshelves lined with somber spines and a sign above it that read Earth Consciousness Library crudely carved into a wide weathered plank. A patchwork of worn and frayed Indian rugs covered a slab floor around which were deployed a variety of mismatched secondhand couches and armchairs and centered on a redwood burl table piled with slick conservationist magazines. The waitress had a large gold stud through the top of one nostril. The way she was made up he could assume that she was on call to perform under the big top. She smiled and it was nice. “Coffee?” and handed him a printed menu with the Sole Sister logo across the top when he nodded yes.

The waitress had a large gold stud through the top of one nostril. The way she was made up he could assume that she was on call to perform under the big top. She smiled and it was nice. “Coffee?” and handed him a printed menu with the Sole Sister logo across the top when he nodded yes. “It’s a murder investigation, Tim, plain and simple, body, gunshot wound, a potential crime scene I’ve been denied access. . . .”

“It’s a murder investigation, Tim, plain and simple, body, gunshot wound, a potential crime scene I’ve been denied access. . . .”

He held it by the length of rawhide and examined it closely. It was the size of a cast belt buckle although solid and crude in its depiction of a face, what looked like a tongue protruding below a bushy mustache, the eyes round with terror or menace. The weight of it belied its size, encrusted in hues of coal black to greenish blues, there was nonetheless something intriguingly authentic about it.

He held it by the length of rawhide and examined it closely. It was the size of a cast belt buckle although solid and crude in its depiction of a face, what looked like a tongue protruding below a bushy mustache, the eyes round with terror or menace. The weight of it belied its size, encrusted in hues of coal black to greenish blues, there was nonetheless something intriguingly authentic about it. Why connecting one dot made him feel like a bloodhound hot on a trail he couldn’t say although it did energized him. He could draw a line from Ike Carey to Dad Ailess by association and by the odd coincidence that Carey was wearing a blue jumpsuit two sizes too small for him, a blue jumpsuit that was described as Dad’s usual attire. Now he had a link between Dad and the vehicle accident the morning Carey’s body was discovered. His next stop was Santa Lena General to learn what had become of the driver of the totaled Mercury. Once he reported his 10-15, the coast deputy arrived to take custody of Billy and await transport to the county jail.

Why connecting one dot made him feel like a bloodhound hot on a trail he couldn’t say although it did energized him. He could draw a line from Ike Carey to Dad Ailess by association and by the odd coincidence that Carey was wearing a blue jumpsuit two sizes too small for him, a blue jumpsuit that was described as Dad’s usual attire. Now he had a link between Dad and the vehicle accident the morning Carey’s body was discovered. His next stop was Santa Lena General to learn what had become of the driver of the totaled Mercury. Once he reported his 10-15, the coast deputy arrived to take custody of Billy and await transport to the county jail. Debbie talked a lot when she was nervous and that made Donovan nervous. “The room was scrubbed soon after they transported, I doubt you’ll find anything. There’s already a new patient in there. And even if I did, I could get in serious trouble if anyone found out I’d let you in. Privacy rights, you know. I don’t know what Maria was thinking.” They were standing by the double doors that led into the ICU. She had her mask pulled down under her chin, a large sterile cap covering a pile of blonde hair, and a full blue gown and matching booties.

Debbie talked a lot when she was nervous and that made Donovan nervous. “The room was scrubbed soon after they transported, I doubt you’ll find anything. There’s already a new patient in there. And even if I did, I could get in serious trouble if anyone found out I’d let you in. Privacy rights, you know. I don’t know what Maria was thinking.” They were standing by the double doors that led into the ICU. She had her mask pulled down under her chin, a large sterile cap covering a pile of blonde hair, and a full blue gown and matching booties.

Donovan followed Delphi Road up the lee side of Mount Oly. The narrow paved road wound around the base of the coastal peak still shrouded in fog. Vistas of dry yellow grass and oak woodlands, dotted in the near distance by grazing animals, stretched on either side broken occasionally by a trailer home set back under a cluster of trees or a barn and some farm machinery. Driveways were indicated by rural mailboxes and posts marked with large red reflector buttons. Some areas included sheds, corrals, and chutes indicating working ranches. Then a manicured hedge, stone or stucco wall and large wrought iron gates spoke of money that could afford to live that far out and not worry about the commute.

Donovan followed Delphi Road up the lee side of Mount Oly. The narrow paved road wound around the base of the coastal peak still shrouded in fog. Vistas of dry yellow grass and oak woodlands, dotted in the near distance by grazing animals, stretched on either side broken occasionally by a trailer home set back under a cluster of trees or a barn and some farm machinery. Driveways were indicated by rural mailboxes and posts marked with large red reflector buttons. Some areas included sheds, corrals, and chutes indicating working ranches. Then a manicured hedge, stone or stucco wall and large wrought iron gates spoke of money that could afford to live that far out and not worry about the commute. identity as law enforcement, of purpose at its most elemental was still there. Gadget porn was not his thing yet there was also something to be said for its effects.

identity as law enforcement, of purpose at its most elemental was still there. Gadget porn was not his thing yet there was also something to be said for its effects. Once he nosed the front end into the gap, he saw that it was the beginning of an obscured fire road. He steered around the rutted unpaved path several hundred yards in to a clearing and a cyclone fence topped with razor wire. Along with an identical red and white sign threatening lethal force and the specific Federal Codes that allowed the authority was another official sign.

Once he nosed the front end into the gap, he saw that it was the beginning of an obscured fire road. He steered around the rutted unpaved path several hundred yards in to a clearing and a cyclone fence topped with razor wire. Along with an identical red and white sign threatening lethal force and the specific Federal Codes that allowed the authority was another official sign. He took a breath. How long ago had he taken that advanced tactical driving course? Something you don’t get much practice doing once you become a detective. He closed on the bumper, aiming the bull bar for the right rear. Current speed dropping to 30 MPH, he had to hit it just right. Activating the lights and siren as a distraction, he wheeled a sharp turn. The bull bar made contact with the outer edge of the Suburban’s bumper. He accelerated, pushing the large SUV off center to deprive the rear wheels of traction. The Suburban went into a skid, swerved to regain control but only ended up facing the way it had come, what Tac drivers euphemistically called a “committed lane change,” both side wheels dangling over the steep drop.

He took a breath. How long ago had he taken that advanced tactical driving course? Something you don’t get much practice doing once you become a detective. He closed on the bumper, aiming the bull bar for the right rear. Current speed dropping to 30 MPH, he had to hit it just right. Activating the lights and siren as a distraction, he wheeled a sharp turn. The bull bar made contact with the outer edge of the Suburban’s bumper. He accelerated, pushing the large SUV off center to deprive the rear wheels of traction. The Suburban went into a skid, swerved to regain control but only ended up facing the way it had come, what Tac drivers euphemistically called a “committed lane change,” both side wheels dangling over the steep drop. The gravel road into Sparta Creek trailer park ran along a wide dribble of questionable water between sand dunes and beach grass, and was accessed from the paved road that wound up to the parking lot of the overlook popular with hang gliders. A few bright colored sails had drifted down onto the wide beachfront as he turned off the coast highway and followed Royce down the narrow track into the nest of antique trailers, really tiny homes, rusty camper shells, and lean-to’s, most supplemented with one or more blue tarps. He didn’t want to guess how many vehicle violations were parked in front of the dilapidated aluminum dwellings. A profusion of surf boards, either atop of dune buggy type vehicles or leaning against old board fences, spoke of the occupants’ preoccupations.

The gravel road into Sparta Creek trailer park ran along a wide dribble of questionable water between sand dunes and beach grass, and was accessed from the paved road that wound up to the parking lot of the overlook popular with hang gliders. A few bright colored sails had drifted down onto the wide beachfront as he turned off the coast highway and followed Royce down the narrow track into the nest of antique trailers, really tiny homes, rusty camper shells, and lean-to’s, most supplemented with one or more blue tarps. He didn’t want to guess how many vehicle violations were parked in front of the dilapidated aluminum dwellings. A profusion of surf boards, either atop of dune buggy type vehicles or leaning against old board fences, spoke of the occupants’ preoccupations. He consulted his notebook. A “white room” was the interior of a cloud and a very dangerous place to be as it was disorienting to the hang glider. Entering the white room was also a term used to signified someone who had died while hang gliding.

He consulted his notebook. A “white room” was the interior of a cloud and a very dangerous place to be as it was disorienting to the hang glider. Entering the white room was also a term used to signified someone who had died while hang gliding.

Donovan headed back to the parking lot after he’d watched the coroner’s assistants turn the body over and load him onto the gurney. Facing up, the corpse did nothing more than confirm that he was a white male. Royce met him at the top of the path.

Donovan headed back to the parking lot after he’d watched the coroner’s assistants turn the body over and load him onto the gurney. Facing up, the corpse did nothing more than confirm that he was a white male. Royce met him at the top of the path.

He heard it first, and the black chattering shape grew larger coming in from the southwest. The chopper swept low over the farmhouse and then back toward the access road where he’d been waiting by his sedan. There was a wide spot in the stubble field beyond the gnarly giant live oak near the entrance to the front yard. A tornado of fine beige dust and sand engulfed the chopper as it set down. The rear passenger door opened once the dust settled and two figures stepped out.

He heard it first, and the black chattering shape grew larger coming in from the southwest. The chopper swept low over the farmhouse and then back toward the access road where he’d been waiting by his sedan. There was a wide spot in the stubble field beyond the gnarly giant live oak near the entrance to the front yard. A tornado of fine beige dust and sand engulfed the chopper as it set down. The rear passenger door opened once the dust settled and two figures stepped out. of the small backyard crowded with a detached garage probably built in the early fifties. It was a sturdy two hundred plus square feet that housed his personal vehicle, a Mustang convertible boy toy, a midlife crisis gift to himself. Maybe the original owner didn’t like mowing the lawn although the piebald patch of turf in the front yard had been well maintained when he bought the place almost twelve years ago. He was the one responsible for its current shabby overgrown neglect. So what was he hiding under the slab? Bodies? Something that had occurred to him more than once. Cop thinking, he called it.

of the small backyard crowded with a detached garage probably built in the early fifties. It was a sturdy two hundred plus square feet that housed his personal vehicle, a Mustang convertible boy toy, a midlife crisis gift to himself. Maybe the original owner didn’t like mowing the lawn although the piebald patch of turf in the front yard had been well maintained when he bought the place almost twelve years ago. He was the one responsible for its current shabby overgrown neglect. So what was he hiding under the slab? Bodies? Something that had occurred to him more than once. Cop thinking, he called it. He remembered the day well, Valentine’s Day. He was on a domestic violence call on the west side of Santa Lena, in an unincorporated neighborhood on High Creek Rd. A rundown two story Queen Anne knockoff in need of some TLC fronted the High Creek address. Just inside the door a shaggy white haired unshaven older gent lay in a heap at the bottom of a flight of stairs. Accident, at first glance, yet the man was naked below the waist, his pants and briefs wrapped around his ankles. That appeared to have been the cause of his fall. At the top of the stairs sat a woman in a wheelchair, close in age to the dead man. With her was a social worker from Adult Protective Services or Apes, as they were sometimes called, a young woman in her thirties with shiny caramel colored hair and a bright green overcoat. She had a pretty face, but it was marred by a frown and severe expression. She was the one who had found the body and called it in. First responders had arrived about the same time as the deputy. They’d both agreed, a coroner’s case. Something the Ape said to the deputy had made him request a detective from Violent Crimes.

He remembered the day well, Valentine’s Day. He was on a domestic violence call on the west side of Santa Lena, in an unincorporated neighborhood on High Creek Rd. A rundown two story Queen Anne knockoff in need of some TLC fronted the High Creek address. Just inside the door a shaggy white haired unshaven older gent lay in a heap at the bottom of a flight of stairs. Accident, at first glance, yet the man was naked below the waist, his pants and briefs wrapped around his ankles. That appeared to have been the cause of his fall. At the top of the stairs sat a woman in a wheelchair, close in age to the dead man. With her was a social worker from Adult Protective Services or Apes, as they were sometimes called, a young woman in her thirties with shiny caramel colored hair and a bright green overcoat. She had a pretty face, but it was marred by a frown and severe expression. She was the one who had found the body and called it in. First responders had arrived about the same time as the deputy. They’d both agreed, a coroner’s case. Something the Ape said to the deputy had made him request a detective from Violent Crimes. Weston County in February was awash in yellow mustard and acacia blooms. A political compromise in the early 20th Century had created Weston County as a trapezoidal wedge between the conservatives of the Anderson County timberlands to the north, and the well to-do liberals in the agri-burbs of Tolay County to the south. Weston was a sampler of both of those ideologies and equally representative in its topography. To the West, Weston was bound by the rugged coast and the wide blue yonder of the Pacific. Consisting mostly of sparsely inhabited timberland vacation destinations and upscale enclaves notched into and around sheer granite oceanside cliffs, it stretched north to the county line as a continuation of the coastal range. The south and east of the county were taken up by arable lands, home to vineyards, orchards, and truck farms encroached on, steadily and year after year, by housing developments and the attendant paving.

Weston County in February was awash in yellow mustard and acacia blooms. A political compromise in the early 20th Century had created Weston County as a trapezoidal wedge between the conservatives of the Anderson County timberlands to the north, and the well to-do liberals in the agri-burbs of Tolay County to the south. Weston was a sampler of both of those ideologies and equally representative in its topography. To the West, Weston was bound by the rugged coast and the wide blue yonder of the Pacific. Consisting mostly of sparsely inhabited timberland vacation destinations and upscale enclaves notched into and around sheer granite oceanside cliffs, it stretched north to the county line as a continuation of the coastal range. The south and east of the county were taken up by arable lands, home to vineyards, orchards, and truck farms encroached on, steadily and year after year, by housing developments and the attendant paving. Nelson indicated the Crime Scene van and the elderly woman seated on the passenger’s side with the door open. “Mrs. Elma Snyder. Lives in the granny unit out back. Didn’t hear a thing. She found the bodies.” And as an afterthought, “The tech, Fisher, knows her.”

Nelson indicated the Crime Scene van and the elderly woman seated on the passenger’s side with the door open. “Mrs. Elma Snyder. Lives in the granny unit out back. Didn’t hear a thing. She found the bodies.” And as an afterthought, “The tech, Fisher, knows her.” The sitting room immediately inside the front door was just as immaculate and well cared for as the verandah. Had it not been for the bodies. The tech had placed yellow A-frame number placards by each of the corpses. Donovan stood in the middle of the room and observed the position of each of the dead men. Number one and two, caught sitting, right between the eyes, mouths still open in surprise. Number three, not quite a center shot and may have been standing by the way he had fallen over the arm of the chair. Four looked like he had a defensive wound on his right hand, but the bullet tore right through it and entered just below the right eye. Number five caught a slug just below the laryngeal prominence and then another at the hairline. The efficiency of the killing was chilling.

The sitting room immediately inside the front door was just as immaculate and well cared for as the verandah. Had it not been for the bodies. The tech had placed yellow A-frame number placards by each of the corpses. Donovan stood in the middle of the room and observed the position of each of the dead men. Number one and two, caught sitting, right between the eyes, mouths still open in surprise. Number three, not quite a center shot and may have been standing by the way he had fallen over the arm of the chair. Four looked like he had a defensive wound on his right hand, but the bullet tore right through it and entered just below the right eye. Number five caught a slug just below the laryngeal prominence and then another at the hairline. The efficiency of the killing was chilling. Woodrow Ames, also known as Woody, was an animal behavior vet who deprecatingly called himself a glorified dog-catcher. A green County issue mesh ballcap held down the explosion of curly red hair that topped his skinny frame. And anyone one who knew Woody would agree with the assessment that he was fastidious about his uniform attire. A neat freak as the not-so polite would say. His new assistant, a young woman, retrieved the wire lasso at the end of a length of pole and he directed her to walk parallel to the fence in plain view of the large mastiff, attracting its attention. In the meantime, he retrieved a long dark case, the kind a pool shark might carry his professional cue in and extracted two long hollow tubes that he fit together to form an even longer tube. One end was fitted with a round rubber mouthpiece. He propped the blowgun on the open window of the driver’s side door of his truck, inserted the dart in the opening of the tube, and positioned himself to aim. His assistant, glancing back over her shoulder once, moved closer to the fence and the dog on the other side that had by then worked itself into a froth of rage.

Woodrow Ames, also known as Woody, was an animal behavior vet who deprecatingly called himself a glorified dog-catcher. A green County issue mesh ballcap held down the explosion of curly red hair that topped his skinny frame. And anyone one who knew Woody would agree with the assessment that he was fastidious about his uniform attire. A neat freak as the not-so polite would say. His new assistant, a young woman, retrieved the wire lasso at the end of a length of pole and he directed her to walk parallel to the fence in plain view of the large mastiff, attracting its attention. In the meantime, he retrieved a long dark case, the kind a pool shark might carry his professional cue in and extracted two long hollow tubes that he fit together to form an even longer tube. One end was fitted with a round rubber mouthpiece. He propped the blowgun on the open window of the driver’s side door of his truck, inserted the dart in the opening of the tube, and positioned himself to aim. His assistant, glancing back over her shoulder once, moved closer to the fence and the dog on the other side that had by then worked itself into a froth of rage.

Donovan shrugged. “It’s a CYA operation. Considering the identity of the road burger, everyone who’s politically connected is going to want to be in on it, if for no other reason than to cover their asses.” He stopped a short distance from the carnage, a crumpled upended vintage sports car. “That an old Porsche?”

Donovan shrugged. “It’s a CYA operation. Considering the identity of the road burger, everyone who’s politically connected is going to want to be in on it, if for no other reason than to cover their asses.” He stopped a short distance from the carnage, a crumpled upended vintage sports car. “That an old Porsche?”

“Yes, when a large wave breaks close to shore it makes a thunderous noise hitting the sand. The ancients called it the ‘bull of the sea.’ They meant Poseidon, of course.” She pointed to the slide show on a flat screen TV mounted on the wall. “Here are some photos of the recent sculptures we assembled. And the artists. And their friends.” She froze a frame with the remote. “And this is Pol.” The photo was of a young, very handsome man with a long dark mane and a captivating demeanor.

“Yes, when a large wave breaks close to shore it makes a thunderous noise hitting the sand. The ancients called it the ‘bull of the sea.’ They meant Poseidon, of course.” She pointed to the slide show on a flat screen TV mounted on the wall. “Here are some photos of the recent sculptures we assembled. And the artists. And their friends.” She froze a frame with the remote. “And this is Pol.” The photo was of a young, very handsome man with a long dark mane and a captivating demeanor. Donovan closed his notebook and turned to leave. “Thanks for your time. Sorry if I inconvenienced you.” He stopped at a small shelf near the entrance to the gallery to look at a bronze statue of a nude woman with a stag’s head that would make a nice base for a table lamp. Inscribed on the pedestal was the artist’s signature, R. Temis.

Donovan closed his notebook and turned to leave. “Thanks for your time. Sorry if I inconvenienced you.” He stopped at a small shelf near the entrance to the gallery to look at a bronze statue of a nude woman with a stag’s head that would make a nice base for a table lamp. Inscribed on the pedestal was the artist’s signature, R. Temis.

The pulled pork sandwich was as good as it got at the barbeque joint Donovan favored in Old Town. Since the Fed had an expense account, he sprung for lunch. Dabbing a corner of his mouth with a napkin, Donovan continued, “It wasn’t originally my call. This is about two years ago. We had a new guy, Hutter.” Butler nodded like he knew the name. “And Collins, who was undersheriff then, had me go in and back him up. Considering that it was at the Horsemen’s compound, he thought that it might be a little intimidating to the new guy. I’d dealt with Herko before so I wasn’t going to be put off by his bullshit.”

The pulled pork sandwich was as good as it got at the barbeque joint Donovan favored in Old Town. Since the Fed had an expense account, he sprung for lunch. Dabbing a corner of his mouth with a napkin, Donovan continued, “It wasn’t originally my call. This is about two years ago. We had a new guy, Hutter.” Butler nodded like he knew the name. “And Collins, who was undersheriff then, had me go in and back him up. Considering that it was at the Horsemen’s compound, he thought that it might be a little intimidating to the new guy. I’d dealt with Herko before so I wasn’t going to be put off by his bullshit.” When they wheeled Herko into emergency he was screaming that he was on fire. He struggled against the restraints on the gurney and finally broke free of them. He careened down the hallway in agony, tearing at his clothes, his cut, his shirt, insisting that he was burning up. An EMT tried to tackle him and got a blast in the chops from an elbow that landed him crumpled against a wall. Security and deputies who were attending a stabbing call joined the fray. They tased him but he merely ripped the barbs out of his skin and continued to rage, batting at anyone who came near him. He raised his dusty leonine head and roared at the ceiling, digging his nails into his bare flesh. He fell to his knees and gasped for breath. Then he was silent and dead.

When they wheeled Herko into emergency he was screaming that he was on fire. He struggled against the restraints on the gurney and finally broke free of them. He careened down the hallway in agony, tearing at his clothes, his cut, his shirt, insisting that he was burning up. An EMT tried to tackle him and got a blast in the chops from an elbow that landed him crumpled against a wall. Security and deputies who were attending a stabbing call joined the fray. They tased him but he merely ripped the barbs out of his skin and continued to rage, batting at anyone who came near him. He raised his dusty leonine head and roared at the ceiling, digging his nails into his bare flesh. He fell to his knees and gasped for breath. Then he was silent and dead. “It’s all there in the report, Tim. The slug they dug out of Nesso was a .223. Stopped right in the center of the heart. The DEA’s undercover confirmed what I suspected. Herko had a trophy room, strictly off limits to anyone not in the inner circle, on the second floor of the compound with a large window overlooking the undeveloped field that abuts to a number of rural dead ends about a mile away, one of them being Willig near where we found Nesso’s body. Herko had a shooting range set up in the room that allowed him to target practice in the vacant lot behind. He had everything in there, competition rifles worth a couple grand easy, tripods, sandbags, scopes, range finders. Looked like he did his own loads, too. Apparently, according to one of my sources, he did a lot of plinking from his perch.

“It’s all there in the report, Tim. The slug they dug out of Nesso was a .223. Stopped right in the center of the heart. The DEA’s undercover confirmed what I suspected. Herko had a trophy room, strictly off limits to anyone not in the inner circle, on the second floor of the compound with a large window overlooking the undeveloped field that abuts to a number of rural dead ends about a mile away, one of them being Willig near where we found Nesso’s body. Herko had a shooting range set up in the room that allowed him to target practice in the vacant lot behind. He had everything in there, competition rifles worth a couple grand easy, tripods, sandbags, scopes, range finders. Looked like he did his own loads, too. Apparently, according to one of my sources, he did a lot of plinking from his perch.

The dog had almost strangled itself on its tether chain trying to get to him when he approached the gate. He couldn’t be bothered and had gone back to his sedan to call dispatch.

The dog had almost strangled itself on its tether chain trying to get to him when he approached the gate. He couldn’t be bothered and had gone back to his sedan to call dispatch. “That’s all they had left at the souvenir shop.” He wasn’t going to tell them it was a present from Miriam, the emergency room nurse he’d been seeing. She’d gone back to Baltimore to live with “her people” as she’d told him. The coast was just too white. Even the black folk were too white. She’d sent him the bobble-head to say that she still thought of him. Not that he was a baseball fan. Miriam knew he cared only for round ball.

“That’s all they had left at the souvenir shop.” He wasn’t going to tell them it was a present from Miriam, the emergency room nurse he’d been seeing. She’d gone back to Baltimore to live with “her people” as she’d told him. The coast was just too white. Even the black folk were too white. She’d sent him the bobble-head to say that she still thought of him. Not that he was a baseball fan. Miriam knew he cared only for round ball. “Right, that’s the Horseman compound right there and home of Jerzy Herkovanic, the president of Apocalypse Inc. So anybody in that neighborhood knows better than to report gunshots or even a gunshot.

“Right, that’s the Horseman compound right there and home of Jerzy Herkovanic, the president of Apocalypse Inc. So anybody in that neighborhood knows better than to report gunshots or even a gunshot.